Made for More

An Argument from Desire

There’s a kind of hunger that sits deeper than your stomach. It shows up when the concert ends, the credits roll, or the weekend trip is over. The ache isn’t about missing a specific thing. It’s about missing something you can’t quite name.

C. S. Lewis had a word for this feeling: Joy—not happiness, not pleasure, but a kind of longing. He noticed it in moments when beauty broke through, like sunlight on a cold morning or the pull of a half-forgotten memory. Joy didn’t stick around. It came like a spark, then left him restless. But instead of dismissing it as an odd mood, he took it seriously. He thought the ache might be telling him something about reality itself.

Start with the obvious: hunger exists, and so does food. Thirst exists, and so does water. Fatigue exists, and so does sleep. Over and over, we find that natural desires line up with things in the world that can satisfy them. This is not an accident. The match between desire and satisfaction is too consistent to dismiss.

Now here’s the puzzle. Underneath all the ordinary desires, we experience desire that everything in this world falls short of fulfilling. We want joy that lasts, beauty that doesn’t fade, love that never disappoints, meaning that never collapses. But the world keeps telling us no. Every fulfillment is temporary. Every victory turns into yesterday’s news. Every good thing fades with time.

If natural desires generally correspond to real things, what should we make of this desire that has no earthly fulfillment? Lewis argued that the best explanation is that we were made for more than the world we see.

Framing the Argument

Philosopher Peter Kreeft lays out Lewis’s idea in the form of an argument:

Every natural, innate desire corresponds to something real that can satisfy it.

Humans experience a natural, innate desire that nothing in this world can satisfy.

Therefore, there must exist something beyond this world that can satisfy it.

This isn’t a trick of logic. It’s not saying, “I want something, therefore it must exist.” Plenty of things I want don’t exist: I want to be super strong, or to teleport, or to have a pet dragon. But those are invented desires, and the mind can imagine anything. The argument is about inherent desires that emerge universally: hunger, thirst, companionship, meaning, beauty, joy. They are woven into what it means to be human.

The claim is modest but striking: if all other natural desires correspond to real things, then this one—the longing for lasting joy and fulfillment—likely points to something real as well.

The Vanity of More

We may think that we simply need more of what I already have. More money. More travel. More relationships. More experiences. But if you’ve ever tried that, you know how the story ends. Even the greatest quantity cannot guarantee the best quality. Satisfaction slips through your fingers. The law of diminishing returns haunts us all.

It’s like chasing the horizon. No matter how fast you run, the line where earth meets sky keeps moving. Sooner or later, you realize that if you want the horizon, you’re going to need something more than running.

That realization can break people. Some sink into nihilism, claiming nothing really matters. And it’s entirely unclear whether that should make us happy or sad. Others attempt to numb the ache with distraction. But even the most noble distractions fail to satisfy.

As the preacher put it, “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity!”

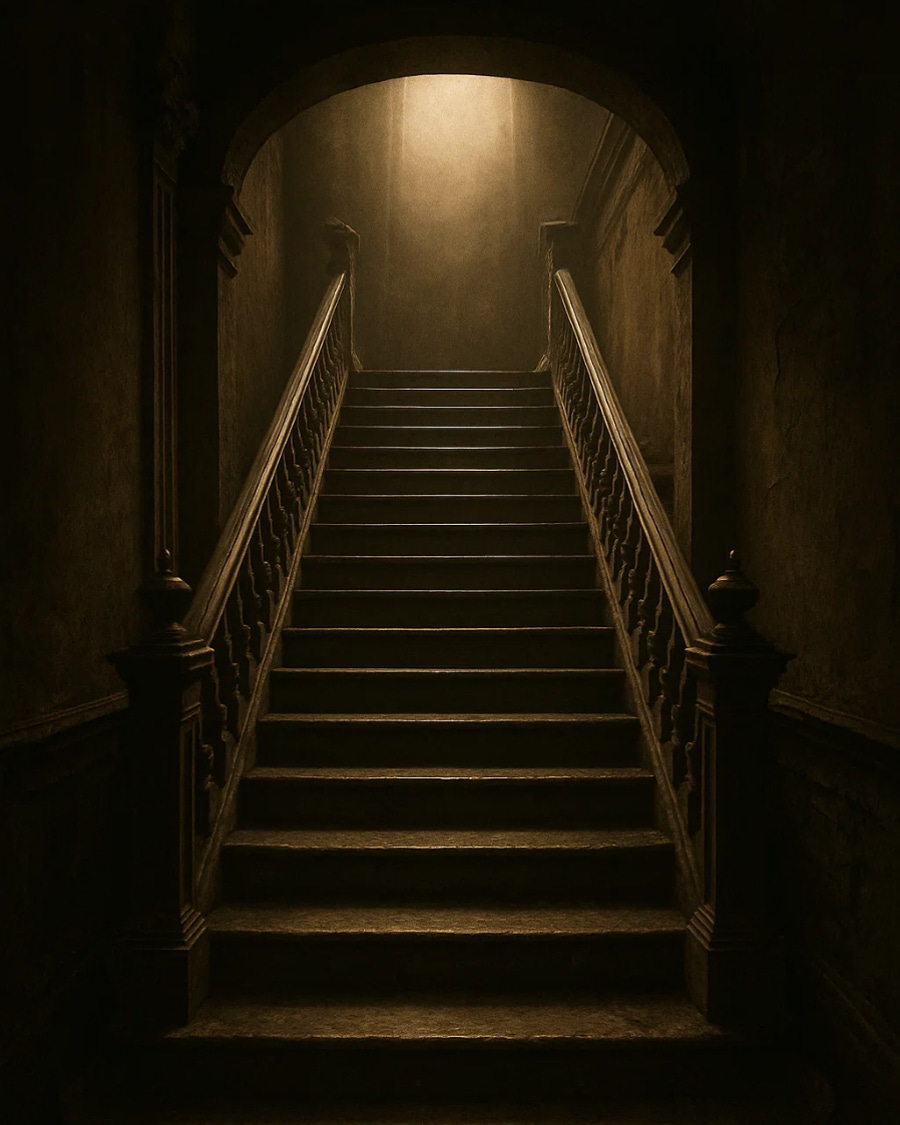

The Weight of Beauty

But then we get a taste of true beauty. A sunset can stop you in your tracks. A song can pull tears from nowhere. For a moment, you glimpse something perfect. But the moment passes, and the perfection slips away. Why does beauty both satisfy and leave us unsatisfied? Why does it feel like a preview of something we’re not allowed to see yet? It awakens a desire but cannot complete it. It points beyond itself, like a signpost on a trail.

A Rational Invitation

One might push back. Isn’t this just wishful thinking? People want there to be something more, so they invent God to make themselves feel better. But that objection cuts both ways. You could just as easily say that people don’t want there to be a God, so they explain away their deepest longings as brain chemistry. This in no way settles the matter. It is only an attempt to explain desire with desire.

But the argument is not about wishful thinking, it’s about explanatory power. If desires consistently correspond to real objects, and if we have a desire that nothing in the natural order can satisfy, then the best explanation is that the object of that desire exists outside the natural order.

As C.S. Lewis wrote, “If I find in myself a desire which nothing in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

This isn’t a knock-down proof. But it is at the very least a clue. An invitation to consider that maybe the world is not a closed system of matter, motion, and chance. Maybe the human heart is tuned to something eternal and infinite.

Living the Question

Imagine a good day: classes went well, lunch with friends, an afternoon run, an evening of laughter. Walking back to the dorm, you look up at the night sky and feel it again—that ache, that sharp awareness that even the best life can’t silence the longing for more.

If you shrug it off, nothing changes. If you distract yourself, the ache will come back tomorrow. But if you ask, “Why do I feel this way?” You’re letting your experience raise the right question about the shape of reality.

Lewis would say that your question is not just personal psychology. It is metaphysics. The longing itself is a kind of argument.

Following the Desire

This argument from desire in no way forces belief. But it does provoke the question. Either the deepest longings of the human heart are absurd, or they are pointing beyond this world.

So, the next time you feel that longing—the ache after joy fades, the hunger no pleasure fills—don’t rush to silence it. Follow it. Ask what it means. The desire may be trying to tell you that you were made for more.